The animated feature film Monster House marks its 15th anniversary this year, and Amblin had the pleasure of reminiscing at length with director, Gil Kenan, about the film’s production and what it’s meant to him and his career.

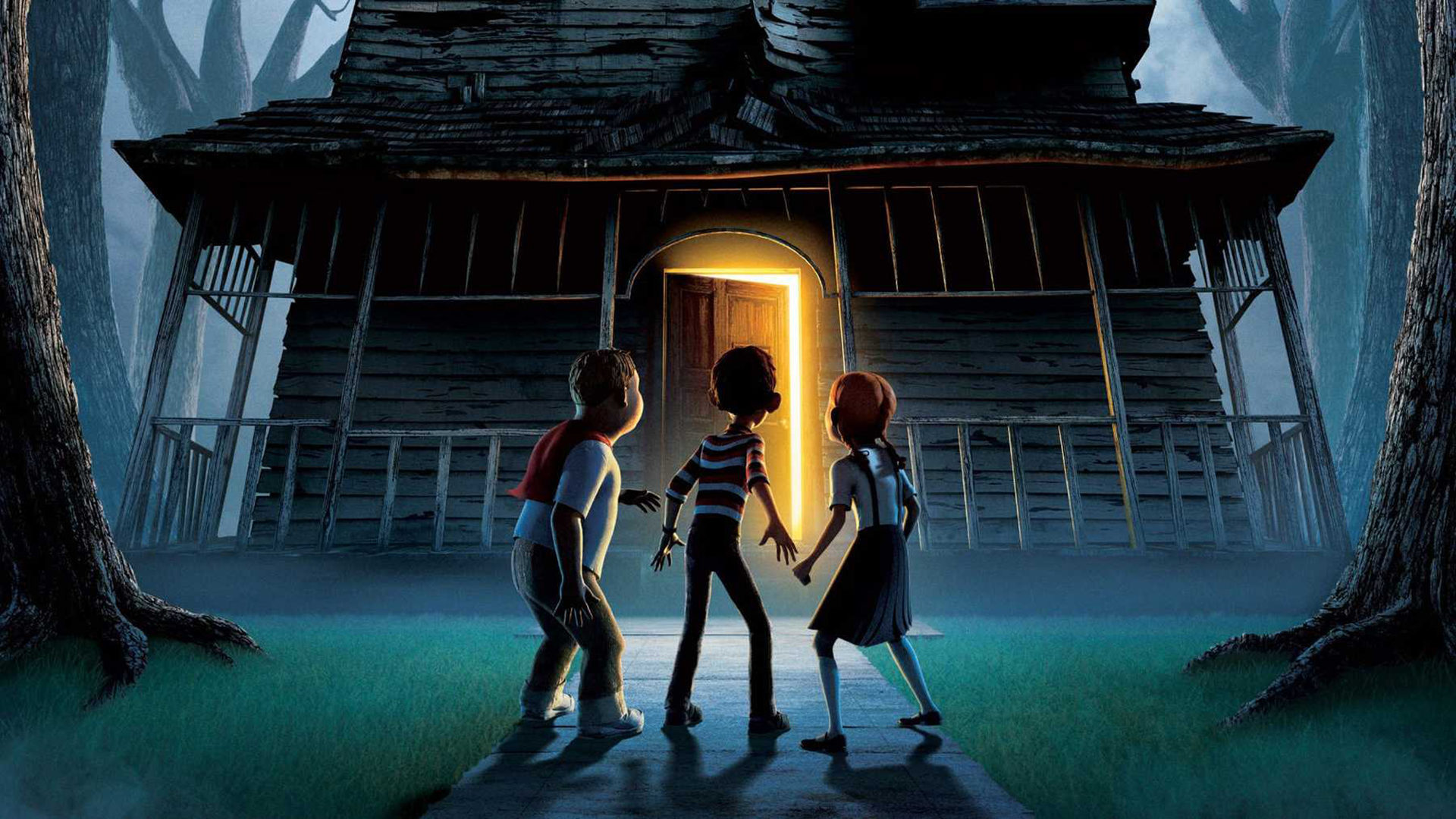

Monster House is the story of young teenager DJ, his friends Chowder and Jenny, and their battle against a creepy house in their neighborhood. The house proves to be more than the normal spooky abode that leads to tall tales and rumors passed amongst kids and adults alike, but a “monster house” in the very literal sense of the phrase.

Monster House is the story of young teenager DJ, his friends Chowder and Jenny, and their battle against a creepy house in their neighborhood. The house proves to be more than the normal spooky abode that leads to tall tales and rumors passed amongst kids and adults alike, but a “monster house” in the very literal sense of the phrase.

Kenan was only a year out of film school when he impressed producer Robert Zemeckis with his pitch for how he envisioned bringing Dan Harmon (Rick and Morty) and Rob Schrab's screenplay to cinematic life, so much so that Zemeckis gave him the reins to direct his very first feature film. Here’s the story of Gil’s journey from film school, to working with Zemeckis and co-producer Steven Spielberg, to releasing what is now considered a spooky season favorite for kids and adults alike.